Study confirms carbon label efficacy: 'They had the predicted effect... lower-emission food choices'

The environmental impact of farming and food production is huge, from cultivation to processing, refrigeration to transportation: a 2012 study estimates the global food system to contribute between 19% and 29% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Nudging consumers to make more sustainable food choices - reducing red meat consumption or swapping exotic fruit flown from the Southern Hemisphere for local, in-season fruit, for example - is therefore crucial to combatting climate change.

However, according to an open-access study published in Nature Climate Change, a severe obstacle to achieving this is the fact that consumers tend to significantly underestimate the environmental impacts of different types of food.

“Consumers encounter food every day; however, the complex production and distribution process is hidden," the US and Australian researchers write. "For example, many consumers may be unaware that cattle release methane, a GHG that is 28–36 times more potent than CO2.”

The researchers wanted to evaluate public understanding of the carbon footprint of food, and if consumers could be encouraged to make more sustainable food choices by a prominent carbon label.

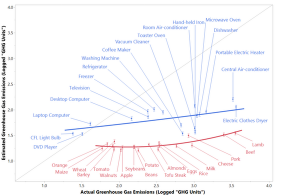

They recruited over 1,000 US individuals and asked them to estimate either the energy consumption or GHG emissions associated with producing and transporting a serving of 19 foods or from using 18 household appliances for one hour.

They found that participants consumers "significantly underestimated" the energy consumption and GHG emissions associated with food production and transportation, and to a greater degree than for appliances.

The authors wrote: “Consumers were relatively insensitive to the difference in energy consumed and GHG emissions of most foods (for example, fruits, vegetables, nuts, milk and cheese), but were relatively more sensitive to the difference in energy consumed and GHG emissions between red meat (for example, beef) and non-meat items (for example, potatoes). Nevertheless, they underestimated red meat by the widest margin.”

The authors hypothesise that this substantial underestimation of food’s carbon footprint is reflected in consumers’ food choices and that people may be unwilling to give up energy-intensive foods such as beef because they do not fully understand the environmental consequences of its production.

Better food choices

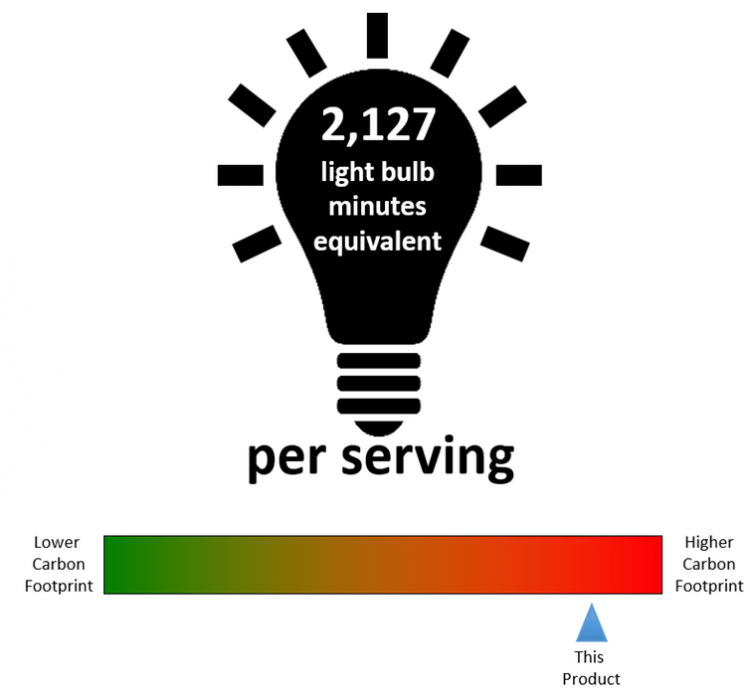

In a second-part study, therefore, they created an easy-to-understand, front-of-pack carbon label that uses a familiar reference unit – light-bulb minutes – to inform food shoppers of the GHG emissions associated with the life cycle of a food product.

They showed 120 individuals a computer-screen menu with six tins of soup – three vegetable and three beef – and asked them to buy three.

The control group was shown the name, serving size, price, calories and macronutrient information about the soups and a picture of each. The label group was given this information as well as a carbon label on each tin.

Two key features for understandable information

The label had two key features, explain the study authors in an article published in The Conversation.

“First, it translates greenhouse emissions into a concrete, familiar unit: equivalent number of light bulb minutes. A serving of beef and vegetable soup, for example, is roughly equivalent to a light bulb turned on for 2,127 minutes – or almost 36 hours.

Do sustainable food swaps really make a difference?

Yes, according to a 2017 study, and not just when people go vegetarian. Clune, Crossin et al. calculated that if the average Australian family replaced ruminant meat (such as beef or lamb) with non-ruminant meat (for example, duck or fish) for one week, they could reduce their food-related emissions by 30%.

“Second, it displays the food’s relative environmental impact compared with other food, on an 11-point scale from green (low impact) to red (high impact). Our serving of beef and vegetable soup rates at 10 on the scale – deep into the red zone – because beef production is so emissions-intensive.”

Ratings were based on the range of actual values observed for soups.

“The carbon label had the predicted effect: those in the label group fewer cans of beef soup than those in the control group,” they write.

“These results suggest that provision of food GHG emissions information in an understandable way increases consumers’ tendency to choose relatively low-emission options compared to when no GHG emission information is provided.

“On average, this information improved understanding of relative GHG emissions between alternatives, which in turn shifted choice towards lower-GHG-emitting options.”

Source: Nature Climate Change

“Consumers underestimate the emissions associated with food but are aided by labels”

Available online, doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0354-z

Authors: Adrian R. Camilleri, Richard P. Larrick, Shajuti Hossain and Dalia Patino-Echeverri