The Presidential Commission to Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) has issued a sweeping challenge to the US food system – placing particular pressure on foods targeted at children.

Central to its agenda is a renewed insistence on ‘gold-standard’ science: the kind that replaces outdated claims and half-measures with credible, evidence-based innovation.

This isn’t just about swapping synthetic for natural or slapping on a cleaner label. It’s about treating public health as a core responsibility, not a convenient add-on. And for bakery and snack developers, it means rethinking everything from formulation and functionality to transparency and trust.

To unpack what this shift demands in real terms, we turned to Anna Rosales, senior director of Government Affairs and Nutrition at the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT).

With deep roots in science, policy and industry, Rosales offers a clear-eyed view on how brands can respond – responsibly and competitively – to one of the most consequential moments the food sector has faced in years.

Why the food industry is under pressure to raise its game

The MAHA Commission (Modernising America’s Health through Agriculture) was established to examine the links between diet, chronic disease and the US food system and to recommend bold new strategies for change. Key themes from its first report:

Call for ‘gold-standard’ science

Research must be rigorous, peer-reviewed and transparent, not selectively interpreted or shaped by industry influence.

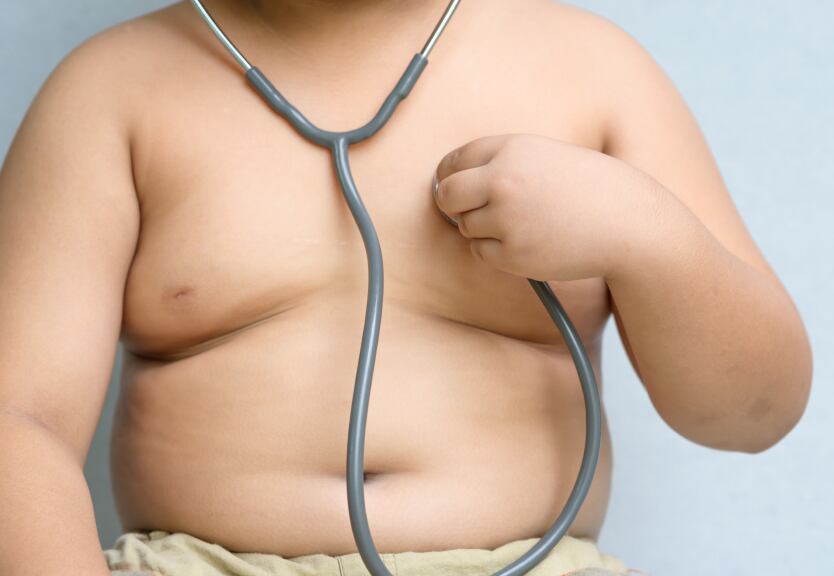

Child health in crisis

Poor diets are fuelling a surge in chronic illness. Over 1 in 5 children over age 6 are now obese: a 270% increase since the 1970s. Prediabetes affects more than 1 in 4 teens, childhood food allergies have risen 88% since 1997; and autism now impacts 1 in 31 children. Childhood cancer rates have increased nearly 40% since 1975. Mental health challenges are also escalating: 1 in 4 teenage girls reported a major depressive episode in 2022; and 3 million high school students seriously considered suicide in 2023.

Food as medicine

A strong push to expand access to medically tailored meals and prescriptions, integrating nutrition more directly into healthcare.

Ingredient oversight

A deeper dive into environmental toxins, food additives and GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) re-evaluations - particularly in ultra-processed foods (UPFs).

Sustainability and equity

The report urges a shift toward a more equitable, accessible and environmentally sustainable food system.

“We will end the childhood chronic disease crisis by attacking its root causes head-on - not just managing its symptoms,” said US Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr. “We will follow the truth wherever it leads, uphold rigorous science and drive bold policies that put the health, development and future of every child first. I’m grateful to President Trump for trusting me to lead this fight to root out corruption, restore scientific integrity and reclaim the health of our children.”

The Commission’s final recommendations - due in 80 days - are expected to reshape FDA policy and food labelling standards, placing new pressure on food brands to act decisively and transparently.

What does ‘gold-standard’ science actually mean?

Let’s clear something up: not all science is created equal.

“Product developers need to prioritise science that’s been through independent, peer-reviewed processes,” says Rosales. “It’s not enough to reference a single study that supports your formulation. You need to look at the totality of evidence.”

And yes, that can take more time. But Rosales is adamant: “We can’t afford to build products on shaky or fragmented data anymore. Consumers – and regulators - are demanding more. If the foundation isn’t sound, the product won’t stand up in the long run.”

Taste, health and convenience: Still a balancing act

With FDA deadlines looming, many producers are scrambling to tweak formulas. But as anyone in product development knows, reformulation isn’t as simple as cutting sodium or swapping in a fibre boost.

“That’s the big challenge – creating products that meet both regulatory and consumer expectations when they don’t always align,” says Rosales. “Taste and convenience still matter deeply to consumers. You can’t ignore that.

“And frankly, the current timeframes aren’t generous. Companies are under pressure to move quickly, but they still need to deliver a finished product that tastes great, fits the budget and meets the new expectations. That’s not easy.”

We’re not just developing products anymore – we’re managing public confidence.

Anna Rosales

Additives, GRAS and the clean label dilemma

One of the most closely watched parts of the MAHA Report is its focus on ingredient safety and transparency, particularly around food additives.

Rosales says the shift away from synthetic dyes – including the industry’s voluntary phase-out of artificial colours by 2026 – is just the beginning. “Consumers are more engaged than ever in what’s going into their food - and they’re asking tougher questions.”

At the same time, the reassessment of GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status is expected to put added pressure on developers.

“This could absolutely slow innovation,” Rosales warns. “If the FDA needs to review more ingredients, they’ll need more resources, more staff, more oversight. But if it’s done right, this increased scrutiny could lead to better transparency and stronger public trust.”

That trust, she points out, is critical. “We’re not just developing products anymore – we’re managing public confidence.”

What about kids?

Products marketed to children are front and centre in the MAHA Report and rightly so. According to Rosales, snack and bakery companies need to take the lead here, using solid science to rework what ends up in school lunchboxes and after-school snacks.

“We’re focused on reducing added sugars, sodium and unhealthy fats, while still delivering essential nutrients like fibre, iron and calcium. You can’t just strip a product down and call it ‘better for you’. That doesn’t work for kids. It has to be smart reformulation, not lazy reformulation.”

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) also come under fire in the MAHA findings, but Rosales urges caution. “We need better definitions and better public understanding. Not all processed food is bad and, in some cases, it’s what keeps food safe, affordable and available. But we do need to be clearer about what’s in our food and why it’s there.”

Trust: Hard to earn, easy to lose

Food producers today aren’t just battling regulations – they’re navigating public scepticism. And it’s getting harder to earn trust, especially when social media can amplify misinformation in seconds.

“Creating a healthier tomorrow and reducing chronic disease in children is not possible without top-level research, innovation and technology,” says Rosales. “That means lifting up food science, not sidelining it.”

But rebuilding trust isn’t just about facts – it’s about empathy. “We can’t just talk at consumers or throw data at them. We need to understand where they’re coming from, engage with their concerns and build solutions that feel honest and human. That’s how you rebuild confidence in food and in the people who make it.”

Keep your eye on the science

IFT is actively working to support the industry through this period of transformation. And while the Commission’s final recommendations are still in the works, Rosales urges companies not to wait.

“Science doesn’t slow us down, it propels us forward,” she contends. “The brands that embrace that will be the ones leading the next era of food.”

For small and mid-sized businesses (SMMEs) who don’t have inhouse food scientists or policy teams, IFT offers practical support through its Concierge Service, connecting brands with regulatory, R&D and formulation experts. Plus, a new digital product development tool is being launched at IFT FIRST in July that aims to make evidence-based innovation easier and faster for all.

The MAHA Commission may have turned up the heat but for product developers, that’s not a bad thing. There’s a real opportunity here to lead with transparency, integrity and science. As Rosales puts it: “This is our chance to build something better – for consumers, for kids and for the future of food.”